NAOMI ROSE, BOOK DEVELOPER & CREATIVE MIDWIFE / Consultations in-person or by phone or Zoom / To contact: Phone: (510) 465-3935 Pacific Time (Oakland, California, USA) / Email: naomirosedeepwrite (at) yahoo.com

The Creative Process

“There is something I need to say. But I won’t know what it is until I say it. And I won’t know how to say it until I let it give itself to me. My esthetic training, my powers of observation, my intuition, my love — all these are elements of what allows what wants to come forth to come forth. But there is Something that draws it forth, the same Something from which it emerges. All this is part of the creative process. And it is available to — even asked of — everyone.” — Naomi Rose

“Great art arrives through the artist’s openness to the unknown and the unexpected, in addition to his or her history of practice and developed skills.” — Elias Amidon, The Open Path

The creative process has fascinated me since I was a child.

As I watched an artist on black-and-white TV named Jon Nagy draw stone arched bridges and water flowing in a stream below, I wondered, entranced, “How does he get something from nothing like that?” Later, I would move into a life with art, in various forms, and find out for myself.

The Creative Process weaves throughout this website, as that is so much of what I do with myself and with my clients.

The mystical aspect of “something from nothing” is also — or maybe I should say, foremost — a place where this question belongs. Because when we give ourselves to the creative process, in which a manifest, often tangible “something” emerges from what before seemed to be just “nothing,” then we too partake of the ultimate and ongoing creative process of the universe, of which we are a holistic (if not holographic) part.

naomi rose knows the creative process of writing a book can be discovered through other media, too

So to fear creating is to turn our backs on the nature of our very being as humans. If we fear creating, it’s because we have been taught to — or have been wounded by the reception to our creating. We can unlearn this, and give our attention to the desire that upwells in us naturally to bring something into being; to express externally something that is in us internally. Not only can we do this, but on some essential level, we must.

Why? Because it is our nature to love, and to bring forth what we love.

When our motivation is love, harmony, and beauty, the process of creating becomes a meaningful, rewarding journey; and the “end result” leads both creator and receiver somewhere true, worth arriving at, no matter what obstacles may have had to be met along the way.

You can learn more about the Creative Process by enjoying the rest of this website:

💮 The Creative Process series of books that I have written — in the Rose Press menu — can help you use writing as your portal into creativity.

💮 Experiencing the art forms I share from my own experience — Naomi Rose Arts (art, writing, music) — will give you a flavor of not only who I am as a creator, but also of who you might become.

💮 Following the creative process of a nonfiction book that I’m writing on the “Behind the Scenes of My Book-in-Progress” page will let you be a close-up participant in how the creative process unfolds (and doubles back on itself, offers itself for revision, and moves forward).

💮 Giving yourself the products in the “Rose Press Enhancements for Writers” Collection will nurture your innate creativity by providing an atmosphere that’s conducive to the organic expression of what’s in you.

So this entire site is devoted to the creative process — through writing a book — as well as to the healing process. As am I, in working with people who come to create the book of their heart.

On this page, I want to share some things about the creative process that you might find worth reflecting on . . . perhaps to the point where you’ll want to try some things out, yourself.

In the following video, I talk about the creative process.

It’s a “homey” video — a good friend came over and recorded me in an informal way.

I hope you will discover things here that are deeply meaningful to you, and experience real encouragement for your flowering.

LEARNING from OTHER ART FORMS

Painting

I have steeped myself in art and music as well as writing over many years. And so I am fortunate to be able to dip into the wisdom and techniques of one art form and translate them, in some way, into another.

‘I often use the analogy of doing a painting to explain how it is possible to write a book out of sequence — perhaps Chapter 8 first (or pieces that later will show themselves to be part of Chapter 8), then Chapter 9, then Chapter 2, and finally Chapter 1.

And it’s not even that linear. Once you trust that you will later find a workable structure for your writing, you can simply follow what interests you, what has aliveness for you, as you write. Then, when you’ve brought forth enough material, you can back up and find out: “What have I written, here? What do these pieces have in common? What seems to be a unifying thread? And what else needs to be written in order to develop the theme that is emerging here?”

Out of that comes tentative structures — Part I, Part II, and so on — that can be tried on to see if they fit what organically wants to be written. There’s a mutual adjustment process that then happens. As something you’ve done settles into its right place, as it resonates with internal rightness, it offers you information about a fitting structure. And as the structure begins to settle in and feel right, it suggests further writing that will make of these pieces a whole.

So the art analogy goes like this:

Imagine you are doing a painting on canvas. Unlike writing, visual art is spatially simultaneous.

You don’t do it all at one fell swoop, but whatever you have done, you can see all at once. So let’s say you have, on your canvas, a green swath of color below, and a blue horizontal swath above. Let’s say this is a landscape, and those swaths of color are your beginnings of grass, trees, and sky.

Okay. Now, as you move closer into the painting, you pick up your brush, load it with perhaps a deeper green, and start making more detailed strokes to indicate blades of grass, more distinct leaves of trees. Now your canvas has a combination of rough color, and the beginnings of detail. While there are all sorts of advised techniques on painting, a common one of which is to lay out the color and shape relationships throughout the canvas before you start in on the detail, let’s say that you are really drawn to delineate a tree on the left, even while the rest of the painting is in rough-color shape. And that you have a moment of pure absorption, putting in the trunk and the roots and the branches and the leaves of that tree.

And that when you’re done, you back up and — oh, it just vibrates!

Well, but there’s the rest of the canvas, still looking like barely a thought. What now?

Now, you allow the tree to inform the rest of what’s on the canvas. The shade of green in the branches — they could be repeated in the grasses, towards the front. And having done that, you may see a place for a hint of colored flowers among the grasses. So you pick up your brush, dab it with red, yellow, and other flower colors, and try your hand at that. Then you back up, get a sense of how it’s all coming together (or not). You try this, you try that. You paint the nuanced blue sky above, and perhaps catch a ray of the yellow you used in the flowers to undergird the sky, a nod to the sun trying to come forth.

And so on. What you do in one part of the painting influences and inspires what you do in the other parts. Some areas, you might end up scraping off or painting over (the writing equivalent is revision); but that’s all right, because there’s a wholeness that’s greater than the sum of the parts that you are seeking to find and make known.

This simultaneity — you might call it a property of the right brain, the holistic brain, or what I have called in my book, Starting Your Book, the “Artistic Brain” — allows you to move back and forth within your creative being without having to make judgments or even many (or any) commentaries on what you are doing. Because you can see the whole emerging as you paint, you hold it in your awareness even as you do the details.

With writing a book, too — although you cannot literally see everything at the same time, or even always hold the whole in your awareness (because sometimes you have no idea where you are going until you begin to come closer to it) — your Artistic Brain knows things, and trusts in things, that your usual linear mind does not.

SPONTANEOUS ART — Being with what the moment gives you

Here is a quote from a painter and watercolor teacher, Barbara Nechis, on working with watercolor. Watercolor, of course, is a very evanescent medium, bringing you into the present moment precisely because it flows and changes so quickly. In fact, the water element, itself, is synonymous with fluidity, flow, and flexibility. (You might keep this in mind when writing your book — that attuning to the water element in you can promote flexibility.)

In her book, Watercolor from the Heart, Nechis gives some beautiful examples from her own watercolor experiments, and discusses her process and her counsel. Here’s one such, from page 16 of her book, the section on “Inner Resources: The Creative Process”:

“I love to experiment. I am challenged by a new piece of paper. I can’t fail because I have no expectations and no preconceived plan. It is more difficult for me to be flexible when I expect a certain outcome.

“Blank paper lies before me. I begin. Initially my mind is a tabula rasa. No thoughts, only feelings. I pick up a brush. I wet all the paper, part of it, or work it dry. I place a stroke somewhere on my page and make a mark. I like it. I make another. What will happen if I extend this shape to the left? What if I bring it out on the other side? Now I remember that shape. It resembles the water at the base of a quarry. Oh! that light down the middle could be a waterfall. Yes, I like it. It is a bit surreal. This shape looks like a bird. Do I really want one? No, I’ll extend the shape to lose the bird. My color is uninteresting. I’ll add orange to my waterfall. Now some pink. How about a purple/black rock? Too dark. I’ll neutralize the area next to it for less contrast. Now some green moss. I need a softer edge.

“What else needs fixing? I don’t know. I’ll come back to it. I go through this process again and again, watching, adding, making changes, thinking.”

Nechis calls this painting “Genesis,” and says of its creative process: “Small flowers appear to spring from the large one. I made the flower centers with spurts of wet paint on wet paper, then let it dry. Next I added glazes for hard edges that would sharpen the image.”

Taking advantage of accidents:

Nechis writes:

“‘Accidents prefer the prepared mind,’ it has been said.

“‘Luck happens,’ [photographer] Ansel Adams observed], ‘when preparation meets opportunity.’

“In a planned or subject-oriented painting, accidents are usually not desired because they must be incorporated into the subject matter to make them work. But in an experimental painting, it is difficult to discern what is an accident and what is not. I welcome most accidents, knowing that although they will make my job more difficult they will also give a special quality to each painting. The accidents are God’s gifts. The challenge is to use them well.”

The painting, “Flower Power,” was just such an “accident.” Nechis writes: “The white shape near the left edge, describing the turn of a petal, was the result of an uneven wetting of the paper. An unwetted spot remained white, so I made use of it.”

Here, the artist takes off on a painting of poppies by Georgia O’Keefe, writing: “While O’Keefe’s influence is evvident in the poppy form, the rest of my painting departs from her florals, emphasizing numerous flowers and shapes.”

“Leaving the cocoon of certainty can be painful for a time, but the rewards can also be great,” Nechis writes.

This is just as true for writing a book. If you knew, at the outset, every single thing you were going to do before you did it, you might have an engineering success, but not as likely an artistic one. The creative process needs to surprise us out of our usual ways of seeing things so that we can open up to inner treasures that we may not have realized were there. And while writing a book is, in so many ways, a different process from doing an experimental painting, we can learn from the playfulness and the open-mindedness of the painting process when writing a book. Maybe some “accident” we stumble upon will open the door to the view we were seeking all along.

INTENTIONAL, DELIBERATED ART — When you’re working towards a desired result

However, not all art is fully this spontaneous. Moments along the way may be, but sometimes artists have a lengthier project in mind, one that requires more time, more thought, more attempts than if doing a spontaneous watercolor. Doing sketches toward/in preparation for the more complete work is a traditional way that artists make their way to the “real thing” (although sometimes the sketches can be quite beautiful and stirring in their own right).

I mention this because writing a book is more like this. If the spontaneous watercolor is more like a poem (though my husband, a poet, will easily revise a poem upwards of a dozen times), then deliberated art is more like a book. There’s an intention, or at least a glimpse of one, and then the steps needed to realize that intention. Such steps are not always clear at the outset — and this is where sketches can come in.

One of my truly favorite painters is Mary Cassatt.

An American who lived in Paris at the time of the Impressionists, at the end of the 19th century. A highly skilled craftswoman in the art of painting, she also was unusual for her time (just being a female artist who was known and respected was unusual for her time) in that she largely painted mothers and their children. Not that this was unusual as a subject, but Cassatt managed to bring such affection and tenderness to the relationship between the mothers and their children, as well as beauty of color, line, and form, that it’s still possible to look at her paintings and engage that tender part of oneself just through that. She is a fine observer — as you’ll see from simply the way the forms incline and touch — and she did many sketches on the way to a more finished painting.

I think we can learn something from this. I’m a bit reluctant to tell you just what. I think you’d do better to just look, and to see what you see, then let that image pass into your stored memory so that — when something of that kind is needed for your own writing process and progress — it can rise up and remind you of it. So much of our artistry, the subtlety of our perceptions, comes not from didactic teachings at all but from observation and awareness of subtle things that call out our own subtler sensitivities.

So here are some of her sketches — paired with the finished painting, when possible. And when not possible (i.e., because I couldn’t find the counterpart), just the sketches; just the paintings. There’s a lot of beautiful noticing here, for you. May it serve your own creating.

Sketches

This sketch on the right is called, simply, “Portrait of a Young Girl.” Notice how it’s mostly a gesture, an indication at this point. I wonder how that might translate into a sketch for your book. . . .

And this next one, below, is called “Mother Jeanne Holding Her Baby.” It has just the barest of pencil lines, just, really, a gesture of the painting to come. Almost just a place-holder. And yet, because great artists tend to give all of themselves to whatever they do, even a preliminary sketch, you can already see in it the beginnings of the relationship between the mother and the child — in the positioning of the heads, the bodies — in the mother’s reflective expression, even in this early, gestural phase.

Now, look at this next one, below and to the right, called — simply and descriptively — “Two Children, One Sucking Her Thumb.” It’s just the barest trace, at this point — except for the more detailed indication of the child sucking her thumb (the other child hasn’t really come into the picture yet). Nevertheless, it has attentive detail and it has heart. Sometimes, in doing visual art, in my experience, the mind can be bypassed in favor of a combination of instinct and feeling. (Not that the mind always must be bypassed, but it may be easier to do so when engaged in the more right-brained act of drawing or painting than in writing, which by definition uses the left brain, the site of language.)

However . . . I show you these drawings to make some analogy (however indirect) to writing a book. Might you consider allowing yourself to “draw,” in your writing, a detail that captures your imagination and heart — and leave the rest indistinct, for now?

This goes against the view (wherever it came from) that every part of the writing — at least the first draft — must be equalized: all filled-in detail, or all a looser weave. But what if you allowed yourself to follow what has the most aliveness for you in the moment, trusting yourself to return later on and fill in what’s needed? Or even let it go (as may have happened in some of Cassatt’s sketches, here, which may not have a corresponding painting that grew out of these earlier indications).

Now, this one, below, called “Reine Leaning Over Margot’s Shoulder,” has enough color and detail that it’s almost more than a sketch. But it’s still a sketch, and it shows how important it is to not hold back in your art (including writing your book) — to give your best to even the sketch, even if you don’t end up using it. This drawing looks to be in pastels — that lovely blurry, smeary, imprecise texture — and it’s signed by the artist, so it’s possible it’s not a sketch at all but a fully finished, intended drawing. But let’s suppose for a moment that it is a sketch: What can this tell us about our own process of writing?

Here are my thoughts; you might give yourself a moment to hear yours:

Perhaps Cassatt began this as a sketch, quickly scribbling in the mother’s inclination, how she leans towards her daughter, the slant of her shoulders, her neck, the downward glance of her eyes. So much is unfinished — and even so, the drawing has a vibrancy and a tenderness. Perhaps what was meant to be a quick sketch became more than that as the artist got into rendering the details of what so clearly held fascination for her skill and for her heart. So that even though the background is only some layered lines of color (mostly green and brown on the light-brown paper), even though the background looks unfinished, the drawing’s heart appeared enough for Cassatt to sign her name.

What does this tell us about what’s possible for ourselves when we write? To give ourselves wholly to what captures our heart, and go as far as we have that light before us and no further? To consider our engagement with our subject (whatever it may be) the arbiter of whether we can “sign our name” to the writing or not? To give everything, even quickly, and then move on without concern for the writing’s “merit”? To love what we love, and force nothing? (And, I would add: to remember that the revision process is always available, and often the difference between an “attempt” and a completed work.)

Almost-completed works (is it a sketch or is it “finished”)?

When one gets used to doing sketches, when it begins to become second nature, the love of the sketching process may bleed into the seriousness of the finished work. The painting to the left, “Picking Daisies in a Field,” is a case in point.

The two figures in the foreground are so beautifully detailed (at least, the clothing is — the faces have that indistinct impression characteristic of sketches) and colored that they suggest a completed work. And yet the background is essentially ignored — it has only some light, faint coloring — a bit of salmon from the color of the mother’s dress, some smoky swirls on an otherwise unattended background. Is it finished? What happens as you look at it? Do you enjoy looking at it? Does something in you want to complete it, to add more color, or a sky, or a grassy area behind?

I’m not advocating abandoning your writing in mid-sentence, or leaving out areas that are needed to make the pieces cohere into a whole. I’m simply noticing that, again, the love of what one creates can vibrate on the page even when — possibly — something else seems missing. On the other hand, Cassatt did go through a Japanese-print period, both ornate and spare, so maybe we shouldn’t rule out the Haiku effect, here. (See the very last painting — lower right — in the set of 12 below, under “Completed Paintings,” to see what I mean.)

It would be forcing things for me to draw out the analogy with writing any further than this. But perhaps you can let this painting/sketch open some doors for you.

Completed Paintings

I deliberately saved these completed paintings of Cassatt for last. I wanted to excite you about the process leading up to them (even if the sketches don’t match the subject of the paintings exactly). I wanted you to see that it’s frequent for an artist (of whatever kind) not to know everything about doing the work at the outset — to have to try things this way and that, to move into what will eventually be the completed work with less certain steps.

Cassatt, to me, is not only a consummate painter but also (as I said before) able to evoke the tender affection that we all cherish, or would like to, between a mother and a child. There’s nothing sentimental about this depicted love: the scenes often involve quite ordinary activities — bathing, sitting, holding, boating. It’s the details that prove the feeling — a true illustration of “God is in the details.” Look, as you view these paintings, at the details: the gestures, the body weight and inclination, the poses of the heads inclining, the smiles, the eyes. And also, the water, the flowers, the clothing, the colors. Not to prize apart the wholeness that forms the experience we get to appreciate, but simply to show how much attention the artist pays to the details that create the experience of wholeness — a feeling of wholeness, as well as a composition of wholeness.

What might that suggest for you in relation to writing a book? And do you think that doing sketches, first — little linguistic sketches, vignettes and scribbles, and maybe even visual sketches preceding the writing — could open you to your feeling heart, and that the heart itself knows how to bring the pieces together?

Enjoy the beauty of these deliberated works.

Music

As suggested above, a book is not a one-time-event creation. How can other art forms help us understand — on various aesthetic, spiritual, and even logical levels — how to move into writing a book; how to offer us a side door into the mystery of creation that is, simultaneously, our birthright?

Perhaps composing a work of music can give us some clues. Because for the most part there are musical structures within which the composer works (unless s/he invents her or his own). In classical music, there are forms that enable certain kinds of music: the fugue, the theme-and-variation, the sonata, the trio, the rondeau, and a great deal more. It might serve us to know something about how some works of music came to be.

But even so, what is the way in which composers compose? Is it the same for all of them? How could it be? Otherwise, it would just be a fill-in-the-blank formula, and that wouldn’t so much interest an artist who is seeking a unique expression of the meeting between the musical toolbox (as a writer’s toolbox is words, including metaphor, vividness of expression, rhythm, tonality — hmmm, this starts to sound a bit musical in its own right) and the soul.

FOR MORE ON THE CREATIVE PROCESS, STAY “TUNED” . . .

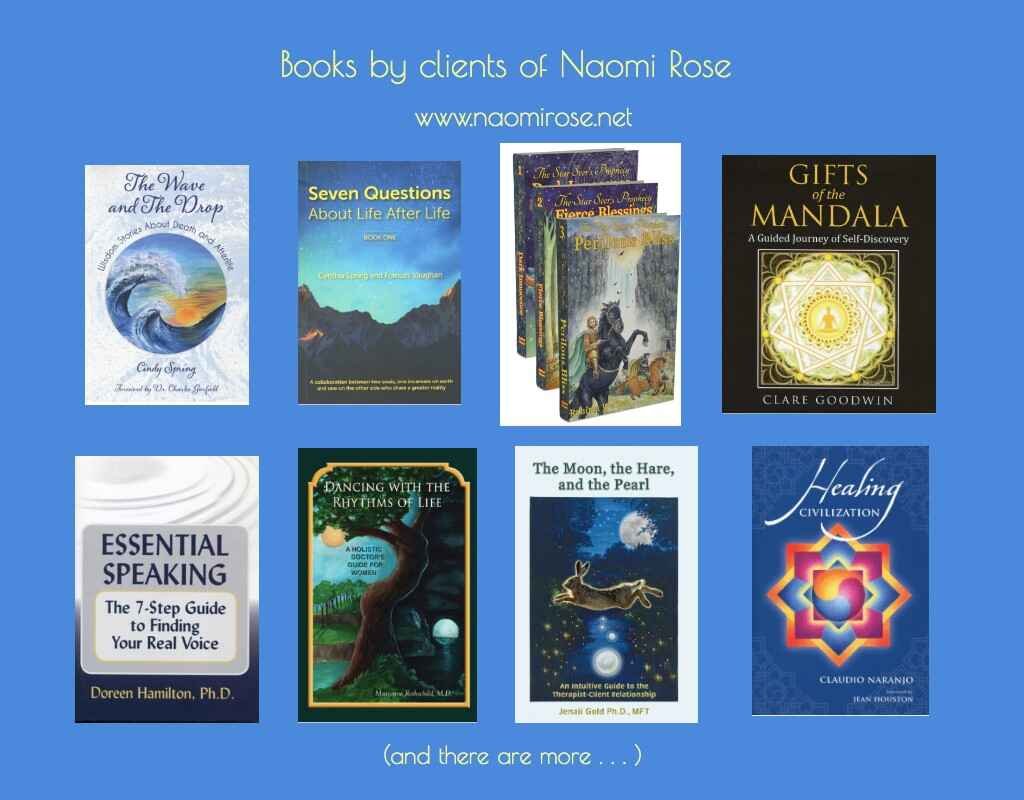

And my own series of books on “The Creative Process”

are inspirational in their own right. They address different aspects of what’s involved in writing a book from the inside out — with the focus on who you are and what speaks to you, so that writing a book can be an outflow of the beauty and wisdom that’s in you (and that gets to show itself to you by your writing the book). These books in the Rose Press “Creative Process” Series are available for your inspiration and encouragement — and to help you make writing a book from the deeper Self a reality in your life.

Starting Your Book: A Guide to Navigating the Blank Page by Attending to What’s Inside You

An Organic Approach to Structuring Your Book: An Alternative to Outlines (Workbook Included)

10 Essential Qualities That Help You Write a Book: A Guide to Watering the Seeds of the Qualities You Need

Starting Your Book opens a path to finding your own path to writing a book and discovering the treasures of your true creative nature in the process.

An Organic Approach to Structuring Your Book lets you say goodbye to rigid outlines and hello to a way to structure your book that lets your innate creativity flourish!

10 Essential Qualities That Help You Write a Book lets you tap into essential inner qualities that help you move beyond perceived limitations so you can work with yourself rather than against yourself — so you can write your book in a way that doesn’t deplete you but instead enlarges you.

To find out more and enrich your own creative book-writing process, click below:

Want inspiration for your creative process?

Sign up for my newsletter and discover the power of writing and healing. Let me support you in bringing the book of your heart to radiant life.

Enter your email address in the box at your left, and click “Subscribe” to join the Writing from the Deeper Self community of like-minded individuals who are committed to writing books that speak to the soul and bring about genuine healing for both writer and reader. You’ll receive expert advice and guidance, creative inspiration, in-depth content, and special offers and discounts. Let your writing be a catalyst for both personal and collective transformation.